Free Derry

After walking around Derry all day, I went north to find someplace to camp beyond city limits. I was hesitant to leave, though. Derry was the last big city I'd see in Ireland and there was a lot of history I missed.

When it started to rain, that made my decision for me. I received some birthday donations from the many great people back home, so I decided to use one, from Vonda, Christy, and Dave in Indiana, to get a room for the night. (Thank you!)

When it started to rain, that made my decision for me. I received some birthday donations from the many great people back home, so I decided to use one, from Vonda, Christy, and Dave in Indiana, to get a room for the night. (Thank you!)

I hovered over my phone to keep it out of the rain while I searched for hostels. Choosing a hostel in Ireland hasn't been that difficult. All of them have been nice, so now I just choose the cheapest one. In America, that kind of reckless behavior can mean sleeping in your sleeping bag to prevent your skin from touching the sheets or wearing your shoes in the shower to avoid whatever the hell.

Due to my preconceptions about hostels and my low expectations, I didn't mind it all that much. It meant I could spend less time working and more time traveling. So far, however, Hostels in Europe have been great. The Derry City Independent Hostel on Princes Street was no exception.

Due to my preconceptions about hostels and my low expectations, I didn't mind it all that much. It meant I could spend less time working and more time traveling. So far, however, Hostels in Europe have been great. The Derry City Independent Hostel on Princes Street was no exception.

The man running it showed me around to the common room, kitchen, restrooms, and where I'd be sleeping. It was a small room with two bunk beds and only enough extra space to walk from the beds to the door. The place was very clean, quiet, and comfortable. On the bottom of one bunk lay the belongings of my new roommate. I set my pack on the other bottom bunk.

When the hostel manager left, I had the room to myself. Before leaving home in 2011, I took for granted how nice it was to sit alone in a room with a roof over my head. I sat on the edge of the bed and as we all do when we have a moment of inactivity, I pulled out my phone to check for messages.

A few minutes later, the owner came back with another guest.

"It will probably be quieter in here," he said. "But the bottom bunks are already taken."

"I'll move up to the top," I said.

"Oh, a gentleman," she said with an accent I thought might have been French. The owner was letting her change rooms because the previous night she had to share a room with a very loud snorer. As nice as the hostels are in Europe, and as much as I loved this one, a bad roommate can make all of that irrelevant.

"Do you snore?" she asked.

"Um," I hesitated. "I've been told I snore quietly sometimes, but I give you permission to kick my bed if I do."

This agreement worked for her, so the hostel manager left. We introduced ourselves. Her name was Yasmine from Algeria. She had been travelling around Ireland for a couple of weeks. When I told her that I was walking across the country, her question was short and to the point.

I've thought about this a lot over the years, and the list of reasons why has grown, but it all really comes down to one thing.

"When I'm hiking, I never feel like I'm wasting my life," I sald. "I love the simplicity of it and it's very freeing to reduce your possessions to only what you can carry."

"When I'm hiking, I never feel like I'm wasting my life," I sald. "I love the simplicity of it and it's very freeing to reduce your possessions to only what you can carry."

"I was thinking I could leave everything," she said. "And I did. Now that I don't have anything, I realize I have needs more than food and bed. I miss some softness and comfort. I miss burning some incense or the light of a candle in my own place."

I thought of how great it felt earlier to be sitting in that quiet room alone under a roof. "I know what you mean," I said. "I appreciate those things more now, though. Maybe you have to lose everything to discover what you really want."

"Some people do," she said. "Others never underestimate their needs."

"But at least when you get rid of everything you figure out what you can live without and what you can't," I said. "That's good knowledge to have."

"That's true."

"That's true."

"So, what do you think of Derry?" I asked, because even though I felt drawn enough to Derry to spend the night, the city depressed me a little.

"So, what do you think of Derry?" I asked, because even though I felt drawn enough to Derry to spend the night, the city depressed me a little.

Derry is where Bloody Sunday took place in 1972. On January 30th of that year, twenty-six civil rights protesters and bystanders were shot by soldiers of the British Army. That wasn't the beginning of the divide in Derry, however, for years the Catholic minority felt they were being discriminated against in regards to employment, voting rights, and in the allocation of public housing. Even 42 years after Bloody Sunday, the peacefulness that exists feels very fragile.

"It seems very depressing," she said. "And I feel tension in the air. I'm supposed to enjoy this Irish trip, not to feel again all the shit human beings can do."

"It seems very depressing," she said. "And I feel tension in the air. I'm supposed to enjoy this Irish trip, not to feel again all the shit human beings can do."

Later, Yasmine would tell me that she left her home in Algeria after years of civil war between Islamic terrorists and the national army.

"There were 200,000 victims in ten years," she said. "This is the number of dead persons, many more people traumatized and thousands of orphans."

"There were 200,000 victims in ten years," she said. "This is the number of dead persons, many more people traumatized and thousands of orphans."

At breakfast the next morning, I found Yasmine and her new friend from Spain, Hilda, in the common area. They were going to tour the city on their own and asked if I wanted to join them.

As we walked through the city, we talked and joked as though we've been friends much longer than a few hours.

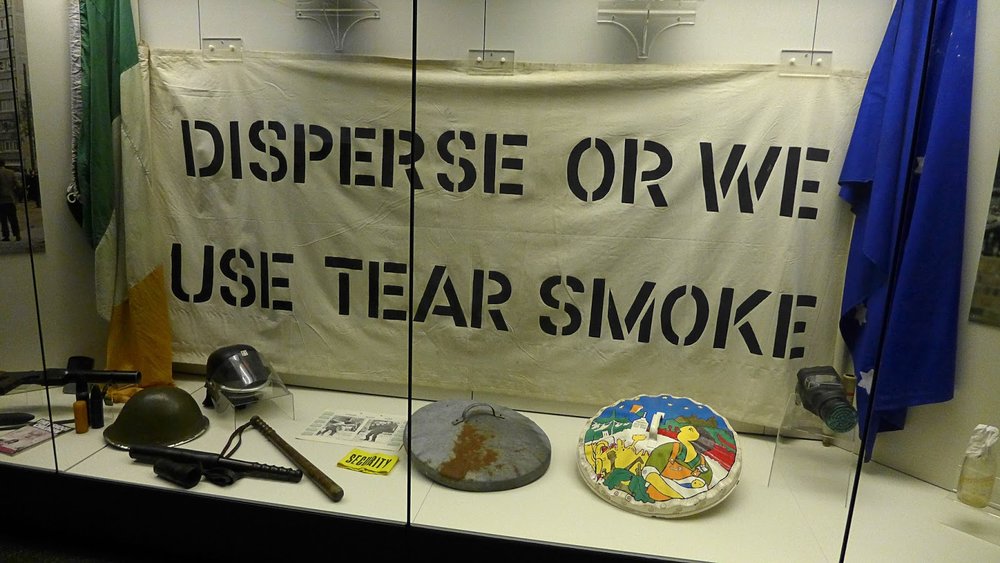

We went to the Free Derry Museum and learned about the events that lead up to, and that happened on, Bloody Sunday. The audio from a video shot on that day played throughout the museum, which a sign warned us about before we entered. After a sobering hour, we walked to the murals painted on buildings all over Free Derry, pictured throughout this post.

We went to the Free Derry Museum and learned about the events that lead up to, and that happened on, Bloody Sunday. The audio from a video shot on that day played throughout the museum, which a sign warned us about before we entered. After a sobering hour, we walked to the murals painted on buildings all over Free Derry, pictured throughout this post.

Since Yasmine had lived through such conflict already, at a much larger scale, she admitted that Derry had not been a happy place for her at first.

"But finally, with your help and Hilda's, I could face Derry," she said. "Like I was not alone to face sad truth. Instead of rejecting Derry, I felt empathy."

|

| Yasmine, Hilda, and me |

After everyone else had gone to bed, Yasmine told me she dreaded her trip coming to an end.

"I feel lost," she said.

I could relate, at least I thought I could. If nothing else, I used the same words before. After spending sixteen months hiking around America beginning in 2011, I admit it was difficult to return to a normal life. On the Appalachian Trail, it's known as the "Post-hike Blues." Each day on the trail had been awe-inspiring and thrilling and back home there were only fragments of my old life, which I had intentionally mangled. I felt like a billionaire who suddenly lost everything. When I left the trail, I lost my wealth. I believed I had one of the best lives on Earth and a confidence that I was doing exactly what I needed to be doing. Then the adventure ended, as they tend to do, and I too felt lost.

I stayed with family, lived in my car, I even lived in a vacuum cleaner repair shop for a couple of months. On the trail, I reveled in having so few possessions. After the trail, I pitied myself for having nothing. I'm glad to say I eventually figured things out, more or less. I'm thankful that I at least had family and a place to go during that time.

"Can you go back home?" I asked.

"To Algeria? No," she said. "This is not an option, Ryan. The civil war stopped because Islamic terrorists became part of government. Killers are now national personalities."

Not being a Muslim didn't make life in Algeria any easier for her either.

"I escaped because of insecurity. As a woman making studies with no veil, I represented Satan."

"Can you stay with your sister in France?"

"My parents say I'm lost and failed in everything because I am not Muslim, so I deserve it. And my sister supports them."

"Whenever I'm around people who have religious beliefs that I don't share, I feel like I'm not allowed to be depressed," I said. "You hide it because you feel they'll just believe your depression is due to your lack of faith. Yet when they are depressed, nobody blames their religion."

"And it's pointless to argue with them because they already know they are right," she said. "I asked an armed person if they would kill me if God asked them to do so. He looked me in the eyes and said, 'Yes, because I'm asked to do so.' There is no need to argue with them."

"Even though I think I already know the answer, and I don't believe you should, why not just wear the veil?" I asked.

"First, it would mean others decide for your own body. Second, to wear veil is like to admit that a woman's body is evil. It's discrimination. Third, it was one of the only ways to resist. They had weapons and they were killing people. We did no war. We were victims. We had no weapons, so not to submit by veil or stopping studies was our way to fight."

"That is incredibly brave."

"That is incredibly brave."

"At that moment, it was less difficult than now," she said. "When I was there, I was part of the majority, now more than 90% of women wear it... They won."

It was getting late. Yasmine, said she needed to sleep since her and Hilda would be getting on a bus to Belfast in the morning. We washed out our coffee mugs and called it a night.

The next morning we all traded contact information. Yasmine is now with her Aunt in France. Hilda, who didn't leave without showing me many great places to hike in Spain, is about to go back to work. She has invited me to stay at her place if I make it as far south as Barcelona.

When we all said our goodbyes and parted ways, it didn't really feel like goodbye. I'll try to see them again on this trip and thanks to living in the age of the Internet, I believe we will remain friends even after we've spread out across the globe.