After, I don't know, six days that I said would be my last in London, I finally made plans to leave the city and start the next phase of this journey. I just had one more stop to make on my tour of important sites in science history, Down House, the former home of naturalist Charles Darwin.

Inside the front door and through the foyer stood a man behind a counter. This man possessed so many English stereotypes that I thought if he were a character on Saturday Night Live, it would offend all of England. I had some difficulty understanding his accent, but he seemed to be saying that picture taking wasn't allowed, so since I had to be stealthy, I was only able to take 330.

I couldn't help myself. This isn't simply the house Darwin lived in, which would have been interesting to me in itself, but this is also where he performed his experiments and developed his theories of evolution by natural selection.

Darwin had a great family life, which anyone who desires such a thing would envy. After his five year voyage on the HMS Beagle, where he visited numerous places around the world to study the plants and animals and collect specimens for future analysis, Darwin's thoughts turned to marriage. He made a pros and cons list and determined that the advantages of marriage outweighed the drawbacks, so asked his future wife Emma to marry him. Who says rational people can't be romantic! Three years and two children later, they moved into Down House where Charles would live out the rest of his life.

Before coming here, I already knew a little about Darwin's life in this house, so was utterly enthralled while walking through these halls.

As I stepped on creaking floorboards, I imagined a time when the silence was filled with the pattering of the ten Darwin children's feet. This was the schoolroom or nursery where the children kept their toys. They were known to climb down that mulberry tree to play outside or help their father with his experiments, which could mean digging holes and collecting earthworms. It sounded like a great childhood to me.

That mulberry tree is still alive and fruiting today.

Darwin became one of my favorite scientific figures, in large part, because of his relationship with his children. Regardless of the work he did, if he was an asshole, I probably wouldn't have cared about coming here. Evidently, Victorian fathers were typically stern and distant, but Darwin was known for enjoying his children's company, playing games with them, telling them stories, and involving them in his experiments.

It was also known, that Darwin viewed his children almost like specimens to be observed. He even kept a systematic journal when his first child, William, was born to keep track of his development. This made me chuckle because I know I would be the same way if I had children.

The death of his ten-year old daughter Anne from Scarlet Fever tormented Darwin for the rest of his life. In a personal memoir he wrote, "We have lost the joy of the household, and the solace of our old age.... Oh that she could now know how deeply, how tenderly we do still and and shall ever love her dear joyous face."

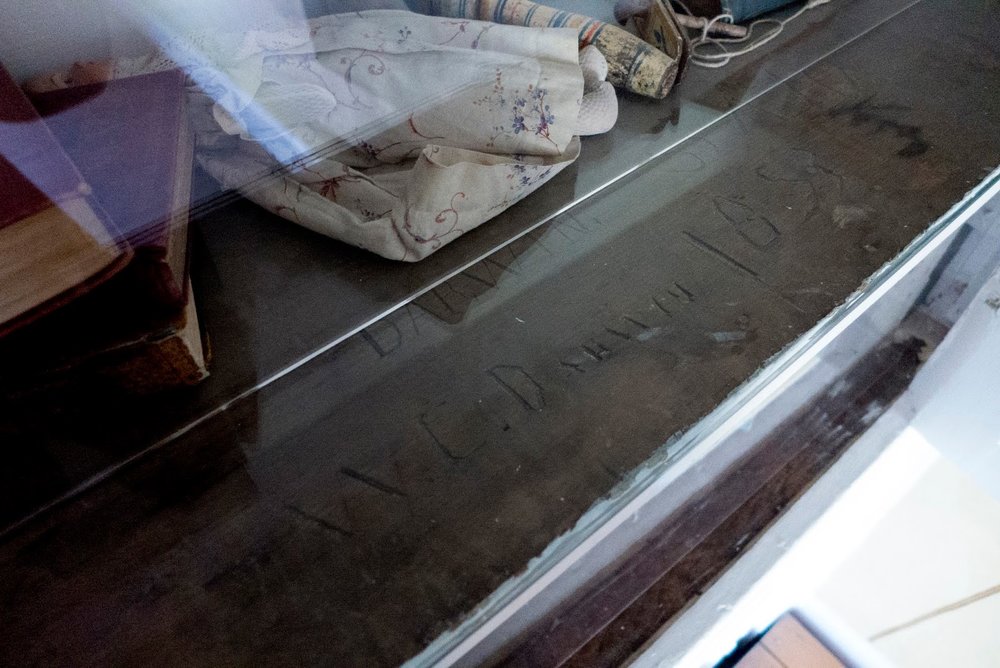

You can still see where William carved his name inside the cupboard in the schoolroom.

I was happy to see a recreation of Darwin's weed garden setup next to the house. It's a good example of the sense of curiosity Darwin had with the natural world and how rather than simply wonder about it, he conducted countless experiments on his property to learn more.

In a letter to JD Hooker in 1857, Darwin wrote, "I am amusing myself with several little experiments; I have now got a little weed garden and am marking each seedling as it appears, to see at what time of life they suffer most."

This simple experiment, along with several others, demonstrated life's struggle for existence and how a lot more organisms are born than survive to reproduce

"...on a piece of ground three feet long and two wide, dug and cleared, and where there could be no choking from other plants, I marked all the seedling of our native weeds as they came up, and out of the 357 no less than 295 were destroyed, chiefly by slugs and insects."

In this book, and in many like it, Darwin made notes on these experiments with the plants in the garden and a variety of other things. On this page shown here, he recorded an experiment testing the resilience of some frogspawn that he did out in the hall.

This infectious curiosity about the natural world is why most of my heroes are scientists. They made me into the nature-loving nerd that I am today. And I love that even in his adulthood, this curiosity sometimes seemed childlike. In his autobiography, Darwin wrote, "...one day, on tearing off some old bark, I saw two rare beetles and seized one in each hand; then I saw a third and new kind, which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which I held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas it ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as well as the third one."

Stories like that make me want to go get my hands dirty.

And it is adventure stories, such as as Darwin's five year voyage on the HMS Beagle, that make me want to explore the world. Darwin's Voyage on the Beagle in particular is responsible for my desire to travel the globe on a great sailing ship (#70 on my life list).

On Darwin's voyage he filled small notebooks with his daily thoughts and descriptions of the places he visited on the journey. When he got back to the ship, he would expand on them and transfer them into this 750-page book. I like to think of this book as Darwin's adventure blog.

By the way, I was excited to see that the audio tour was narrated by David Attenborough...

The Darwins didn't like the house at first, calling it ugly and not old nor new, but it was far enough from the city without being too far, and the house and grounds were large enough to raise a big family.

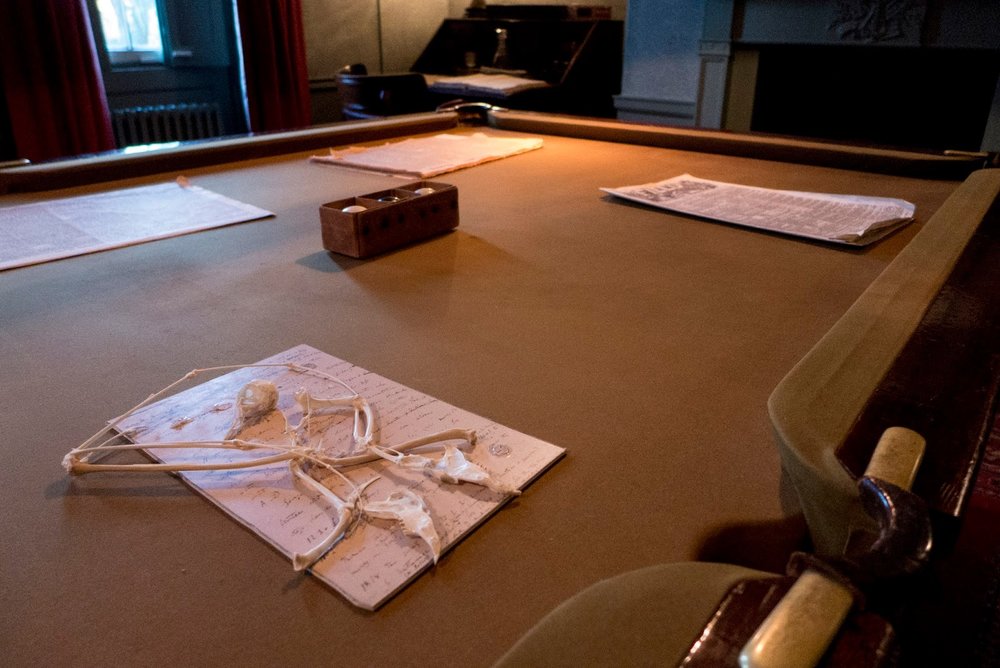

They added this dining room later on and the original dining room became a billiards room.

Darwin discovered that playing billiards was a great way to clear his mind or contemplate something he was working on. He would often stop his work and call one of his servants into the room to play, which both of them loved.

He would also use the pool table as a workspace when he needed more room.

This is believed to be his bedroom and the room he passed away in at the age of 73. It is now a room with interactive exhibits to explain how evolution by natural selection works. I already know how it works, so I was more interested in the windows. As a man who thoroughly enjoyed the land he lived on, who was fascinated by nature, and who loved to watch his children play, I suspected that Darwin often stood staring out of this window, so I had to as well.

Although not in love with the house itself, it seems to be the land that attracted them to Down House the most. Emma was passionate about her gardening, which are maintained today to replicate how it probably once looked, although it was unfortunately too late in the year for me to see it in full bloom. As for Charles, he said, "The charm of the place to me is that almost every field is intersected (as alas is our's) by one or more foot-paths— I never saw so many walks in any other country."

We are all taught that it was Darwin's observations of the tortoises and finches on the Galapagos Islands that were the key to developing his theories, but it was mostly in this greenhouse and in the surrounding meadows and woodland where he would build the body of evidence to prove his theory.

Darwin's beloved greenhouse has been beautifully restored. More of his experiments have been recreated here as well. I walked in right at sunset, the perfect time for photos.

Down a small flight of stairs is Darwin's restored laboratory.

They even continue to grow vegetables in the Darwin's kitchen garden as well as rows of primulas to replicate an important study on plant evolution. All that was left in the garden this late in the year was this moss curled parsley.

If you continue down this path in the opposite direction you'll find Darwin's thinking path that he called the Sandwalk. I walked on it for a short distance, but unfortunately ran out of time and had to turn back. I was too fascinated by every little thing to remember that walking the Sandwalk was one of the main reasons I wanted come here. I have had a few thinking paths in my life. Like Darwin, I have found walking to be good way to ponder ideas, worries, or to just clear my head. Although, admittedly, my ideas and worries are considerably less profound.

I saved my favorite part of this tour for last. In this study, while sitting in that chair, Charles Darwin wrote, On the Origin of Species, the most important biological text in history, prob in all of science. In it, he presents the scientific theory that populations evolve over the course of generations through a process called natural selection. It includes evidence gathered on the HMS Beagle voyage and his findings from experiments, research, and correspondences gathered while living and working at Down House.

Since it was the best source of light in the house, Darwin built this table for his microscope.

The first edition of the book and pages from the original manuscript were on display in the museum upstairs.

He waited twenty-three years to present this work to the public, possibly in part because of the religious implications of demonstrating how species evolved from one another, as his wife was deeply religious, but it seems more likely that he wanted to be sure he preempted all of the counterarguments that were sure to come from his colleagues from such a controversial theory.

I've never understood why this controversy is still so wide-spread in America today, given the evidence is demonstrably clear, and that many religious people today happily accept the theory, believing God to be the cause of life and evolution the product.

As for me, I revel in knowing that all life on earth stems from a common ancestor, that all life is connected in a very real way, that we share so much of our genetic makeup with every ape and apple tree, with every orchid, butterfly, and banana plant. To not have this knowledge carefully accumulated at Down House, and other scientists in the 150 years that followed, the world might somehow seem a little bit less beautiful, less mysterious, less worthy of my absolute reverence and awe.

This ended up being my favorite stop around London. Although there is a lot more I could explore here, I'll save it for another time. I was finally ready to leave it behind me for now. I got back on my bike and rode toward another hostel, thirteen miles away on chilly dark streets, with the excitement and concerns for the following day swarming around in my head.