Part 3: Monday on Old Rag Summit

Part 3: Monday on Old Rag SummitGo to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

Just after sunrise, I unzipped my sleeping bag and mourned the release of the sleep warmth inside. I poked my head out of the tent; the cold cloaked my face. The quiet flow of water, the echoing birdcalls, and the promise of breakfast hanging safely in a tree, put me in a joyous mood.

I poured a cup of water and powdered milk into a zip-top bag of cereal, then unfolded my map in front of me to review today’s hike. On the trail, even the simplest breakfast becomes a delicacy that you crave. I’m coming back to this spot tonight, so don’t need to take much with me. I sorted through my gear and decided what I could leave behind, and topped off my water at the creek.

After a two-mile hike from camp, I arrived at my trailhead and began to snake up the mountain on switchbacks. Half a vertical mile above me awaited my destination, the summit of Old Rag.

An hour later my path ran into mounds of bedrock and boulders like elephant backs. I put the hiking poles away; I would need all fours for this one.

On my right, the trees were occasionally parted like curtains framing the mountains. I stopped to take a photo and two middle-aged hikers passed me.

On my right, the trees were occasionally parted like curtains framing the mountains. I stopped to take a photo and two middle-aged hikers passed me.“I picked this vacation, so what’s your choice for next year?” The exhausted man asked his wife. She paused to suck in some oxygen and declared, “A cruise!”

Birds hiding in bushes fluttered away as an expansive view of the valley opened up before me. Hundreds of feet below the sweeping view of forested hillsides, sprawled a patchwork of rural Virginian farmland. It was a good spot for a break.

Soon a fellow hiker, who I will forever refer to as Paul (even though I actually have no idea what his name is) stopped to have lunch. Paul was an EMT, which was nice to learn. When is hiking in close proximity to an emergency medical technician ever a bad thing?

“Is that the summit?” I said pointing up the ridge at a huge rock jutted skyward.

“No, you still have a ways to go. There are a few false summits actually. This trail is a lot more challenging than people think. I’ve even seen kids trying this trail in flip-flops,” he scoffed while pulling out an orange. “I was hiking with a buddy of mine one year and a woman fell and cracked her head open against a rock." He dug his fingers into the orange rind, spraying a mist of juice, and slid his thumb underneath to peel it back, adding graphic imagery to his tale. "It took us nine hours to get her down from here. A helicopter came, but they couldn't land very close by. So, we carried her to it.”

“No, you still have a ways to go. There are a few false summits actually. This trail is a lot more challenging than people think. I’ve even seen kids trying this trail in flip-flops,” he scoffed while pulling out an orange. “I was hiking with a buddy of mine one year and a woman fell and cracked her head open against a rock." He dug his fingers into the orange rind, spraying a mist of juice, and slid his thumb underneath to peel it back, adding graphic imagery to his tale. "It took us nine hours to get her down from here. A helicopter came, but they couldn't land very close by. So, we carried her to it.”“I try to help when I can,” he pointed at a backpack with a coil of thick nylon rope clipped to the side, “but I only bring a first aid kit and 100 feet of rope with me, so I can only help so much.”

A few minutes after some dispiriting medical dramas, I picked up my backpack. “We’ll, I’ll let you enjoy your lunch. I’m going to continue on.” Sliding the pack on my shoulders, I started up the trail. “My name’s Ryan by the way, so now if you see a body on the rocks below you'll know what to call me.”

“I’m Paul,” he said in an almost demanding tone that didn’t make sense to me at the time.

“I’m Paul,” he said in an almost demanding tone that didn’t make sense to me at the time.“Nice meeting you.” I waved and proceeded up the trail.

“Oh,” he called back. “You’re going to get to a narrow ravine. Look for a little handhold on your left; it will help you get down,” I thanked him for the information. He turned back to the view and dropped an orange wedge into his mouth.

Wait, he didn't say "I'm Paul", he said "don't fall". Oh well, the name stuck. He's Paul whether he likes it or not.

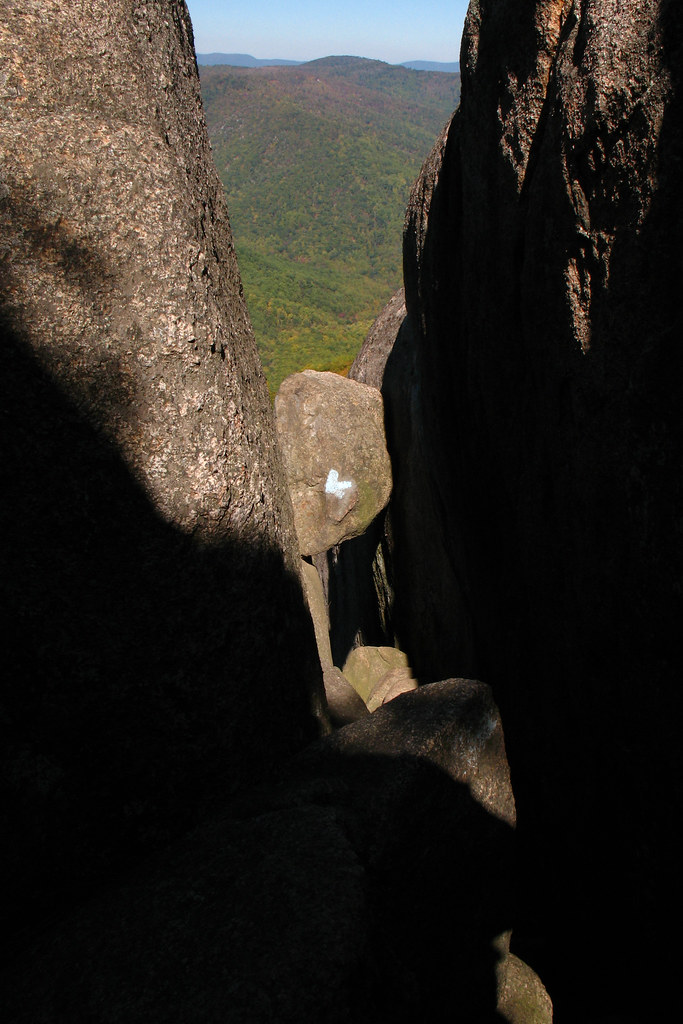

At a shallow ravine two or three feet wide, I paused to figure out the best way get down. Realizing this is where Paul was talking about, I looked to my left. Sure enough, there was the handhold on the opposite side. I lowered my backpack and hiking poles into the ravine. I sat down, legs dangling over the edge, and slipped my left fingers into the handhold and slid in. I dropped onto the large boulders resting in the bottom, happy I didn’t smack my face on the rock wall.

My shoulders bumped along the sides as I hiked a short distance to the much shallower end. A small blue arrow spray-painted on a boulder directed hikers to the left. I threw my gear over the ledge and climbed out.

My shoulders bumped along the sides as I hiked a short distance to the much shallower end. A small blue arrow spray-painted on a boulder directed hikers to the left. I threw my gear over the ledge and climbed out.The trail twisted through a maze of granite slabs and enormous boulders. Often, I had to take my pack off to slide sideways through narrow gaps between rocks toward slivers of light at the other end.

I stopped at a smooth round boulder, as tall as me, that blocked the trail . It leaned against a granite wall to the right, and on its left was a steep drop. I struggled to think of a scenario where I got on top of this thing. “Surely there’s another way around it,” I thought, but there wasn’t. I had to get on top.

I could hear voices. “…took us nine hours to get her out.” It was Paul, who had passed me at some point earlier on, telling the same story to other hikers. If they could get up there, then I believed I could too. And if I was lucky, I could get passed it before Paul told them all the ways you can die up here.

I threw my gear on top of the rock and out of the way. I tried jumping and pulling myself onto it but it was too large, too slick, and too round. I tried once again while kicking off the granite wall next to it. I grabbed for anything to pull myself up but slid back down, skin scraping on rock. The third time I got a short running start and once again jumped kicked off the wall with my right foot. This time, I got my forearms and elbows on top. I knew I could make it now. I pushed up on my hands, got my knee under me, and crawled the rest of the way up. I felt very proud of myself. I felt like an accomplished seasoned hiker. I felt like Ninja Gaiden. And bruised, I also felt very bruised.

It was a beautiful day. The chill had gone. I removed my jacket, but still sweat profusely. I hid behind a rock and took off my base layer and got down to just a t-shirt and pants. I was so happy to be warm for the first time in days.

On a level area of exposed bedrock, with a clear view of the valley, I stopped to take a break. Paul was standing there taking advantage of the cell phone reception.

On a level area of exposed bedrock, with a clear view of the valley, I stopped to take a break. Paul was standing there taking advantage of the cell phone reception.“How you doing?” he asked while stuffing his phone back into his pocket.

“Pretty good. Just a little trouble getting over a giant rock back there, other than that no problems.”

“Oh yeah, I know where you mean. That’s where that woman fell and busted her skull. They had to land the helicopter right here actually. We carried her all this way.” It was good to be in one piece, bones intact, with only the regular holes in my skull. And really how often are you reminded of how great it is to not have a gaping head wound? Thanks Paul.

He warned me about missteps, loose gravel next to dizzying cliffs, mountain lions, bears, poisonous snakes, raccoons stealing your only food, and any other unlikely fatal scenario that came to mind. I know occasionally someone is seriously injured or killed in our national parks, but people also die on toilets, in bowling alleys, at all-you-can-eat Chinese buffets and in Wal-Mart parking lots. Dying on a beautiful mountain range seems a far better way to go than dying like Elvis, or the thousands a day spending their last hours in hospital beds hooked up to beeping monitors.

The drive to the park is far more dangerous. Only about 100 of the 275 million people who visit the national parks each year will suffer a fatal injury, and it’s safe to say alcohol and stupidity inflate that statistic. It’s absolutely something to prepare for, but it’s just not something worth worrying about. Paul seemed preoccupied with it. I suppose being an EMT means you’re going to see it and think about it more often than most.

Even though I'm regularly guilty of taking the path with the least resistance in life, I believe it’s important to be unafraid to take a small risk now and again. I’d rather live a short adventurous life, than a long repetitive one, with the regret that I've wasted all my youth and good health.

If only I could have pulled from memory one of my favorite John Muir quotes to end my conversation with Paul. “Accidents in the mountains are less common than in the lowlands, and these mountain mansions are decent, delightful, even divine, places to die in, compared to the doleful chambers of civilization. Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Fear not, therefore, to try the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action. Even the sick should try these so-called dangerous passes, because for every unfortunate they kill, they cure a thousand." Nobody says it better than John Muir.

If only I could have pulled from memory one of my favorite John Muir quotes to end my conversation with Paul. “Accidents in the mountains are less common than in the lowlands, and these mountain mansions are decent, delightful, even divine, places to die in, compared to the doleful chambers of civilization. Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Fear not, therefore, to try the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action. Even the sick should try these so-called dangerous passes, because for every unfortunate they kill, they cure a thousand." Nobody says it better than John Muir.

A couple false summits came and went, but I was getting close. I felt more confident on the rough terrain now. I hopped onto boulders and over thin ravines like an old pro. When I got to the top, I was both overjoyed and a little saddened that one of the best trails I’ve ever hiked had ended.

On large boulders sat a scattering of day-hikers. Some of them were eating their lunches, while others sat with arms around a loved one just looking at the view. I found the boulder I thought was the highest and scrambled as close to the top as I could. I began nearly half a vertical mile down. Why stop with only a few more feet to go?

Even though I'm regularly guilty of taking the path with the least resistance in life, I believe it’s important to be unafraid to take a small risk now and again. I’d rather live a short adventurous life, than a long repetitive one, with the regret that I've wasted all my youth and good health.

If only I could have pulled from memory one of my favorite John Muir quotes to end my conversation with Paul. “Accidents in the mountains are less common than in the lowlands, and these mountain mansions are decent, delightful, even divine, places to die in, compared to the doleful chambers of civilization. Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Fear not, therefore, to try the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action. Even the sick should try these so-called dangerous passes, because for every unfortunate they kill, they cure a thousand." Nobody says it better than John Muir.

If only I could have pulled from memory one of my favorite John Muir quotes to end my conversation with Paul. “Accidents in the mountains are less common than in the lowlands, and these mountain mansions are decent, delightful, even divine, places to die in, compared to the doleful chambers of civilization. Few places in this world are more dangerous than home. Fear not, therefore, to try the mountain passes. They will kill care, save you from deadly apathy, set you free, and call forth every faculty into vigorous, enthusiastic action. Even the sick should try these so-called dangerous passes, because for every unfortunate they kill, they cure a thousand." Nobody says it better than John Muir.A couple false summits came and went, but I was getting close. I felt more confident on the rough terrain now. I hopped onto boulders and over thin ravines like an old pro. When I got to the top, I was both overjoyed and a little saddened that one of the best trails I’ve ever hiked had ended.

On large boulders sat a scattering of day-hikers. Some of them were eating their lunches, while others sat with arms around a loved one just looking at the view. I found the boulder I thought was the highest and scrambled as close to the top as I could. I began nearly half a vertical mile down. Why stop with only a few more feet to go?

I stuffed an energy bar and my journal into a pocket before climbing up, then sat for a while writing and eating next to the breathtaking 360-degree view, the Blue Ridge Mountains on my left, and rural Virginia Farmland on my right.

I hiked through Weakly Hollow on my journey back down to camp. A much less challenging hike, but there were fewer people. Actually there were no people.

For the remainder of my hike, the sky stayed blue, but the trees’ shadows lengthened and began to darken the forest floor. The hike was peaceful, mainly due to the absence of humans, but also the lack of any unnatural noise, something you forget is greatly important until you're experiencing it. I could hear the tiniest sounds as birds fluttered from branch to branch and rodents bustled along the ground. The wind rocked the treetops back and forth while their drying leaves shivered and hissed, as calm as ocean waves.

Part 4 >

Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

I hiked through Weakly Hollow on my journey back down to camp. A much less challenging hike, but there were fewer people. Actually there were no people.

For the remainder of my hike, the sky stayed blue, but the trees’ shadows lengthened and began to darken the forest floor. The hike was peaceful, mainly due to the absence of humans, but also the lack of any unnatural noise, something you forget is greatly important until you're experiencing it. I could hear the tiniest sounds as birds fluttered from branch to branch and rodents bustled along the ground. The wind rocked the treetops back and forth while their drying leaves shivered and hissed, as calm as ocean waves.

Part 4 >

Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7