Part 7: Friday’s Journey Home

Part 7: Friday’s Journey HomeGo to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

I didn’t sleep well. I partially blame setting up camp after dark. My sight was limited to what was revealed in the beam of a miniature headlamp. The wind flapped the rain tarp all night, like someone trying to get sand off a beach towel. Eventually, I gathered enough motivation to slip out of my hammock and the warmth of that artificial down and nylon womb, also known as a sleeping bag. I crunched the cold and dry autumn earth, with my bare feet, and tried tightening the guy lines in the faint cerulean moonlight.

After falling back asleep the flapping began again. My groggy attempt to fix the situation with cold fingers and low light failed, but a combination of warmth and tiredness kept me from trying again. I slept as deep and undisturbed as a morning repeatedly hitting the snooze bar instead of turning off the alarm clock. Yeah, I don’t know why either. Sometimes I’m surprised at how unwavering my desire to stay in bed can be.

Many of the same elements that caused the frustrations the first night were back: the issues securing my bear bag, setting up camp in cold darkness, and the sporadic intervals of sleep. Only now, frustration and worry wasn’t getting any traction in my mind. This wasn’t a conscious effort, but the result of a reclusive week on a trail where your only task is to walk, where the noisy neighbors are the multitudes of singing birds, the traffic is an occasional white-tail deer or black bear, and your important meetings are with infinitely patient waterfalls.

Many of the same elements that caused the frustrations the first night were back: the issues securing my bear bag, setting up camp in cold darkness, and the sporadic intervals of sleep. Only now, frustration and worry wasn’t getting any traction in my mind. This wasn’t a conscious effort, but the result of a reclusive week on a trail where your only task is to walk, where the noisy neighbors are the multitudes of singing birds, the traffic is an occasional white-tail deer or black bear, and your important meetings are with infinitely patient waterfalls. When there was enough light to pack, I finally got up. For a short time I sat sideways in my hammock with my feet dangling a few inches above the ground. The rising sun turned the clouds to bright coral and revealed the surroundings to me for the first time. The dominant presence was that of a large tree with thick low branches stretching out perpendicular to an old wide trunk. It stood alone in a treeless circle on the forest floor, like a statue of Saint Francis in a courtyard holding out his arms to provide a place for birds to perch. I slipped on my shoes. The tree needed to be climbed.

When there was enough light to pack, I finally got up. For a short time I sat sideways in my hammock with my feet dangling a few inches above the ground. The rising sun turned the clouds to bright coral and revealed the surroundings to me for the first time. The dominant presence was that of a large tree with thick low branches stretching out perpendicular to an old wide trunk. It stood alone in a treeless circle on the forest floor, like a statue of Saint Francis in a courtyard holding out his arms to provide a place for birds to perch. I slipped on my shoes. The tree needed to be climbed.I felt like the seven-year-old Ryan running around the neighborhood where I grew up. I climbed to the first branch and stood on its coarse bark in untied shoes. I began to find my way to the next height, at least until my brain rationalized what would happen if I fell. This isolated spot, at least a hundred yards from the trail, may not see another visitor for days or, this time of year, weeks, maybe not until spring. Rationalizing-adult Ryan sat on the branch and swung his feet back and forth above the ground, at a height that wouldn’t kill him. Rationalizing-adult Ryan is no fun.

A blanket of low gray clouds began to slip under the cheery coral ones, essentially ending any chance that the sun’s rays would chase away the chill; it was sure to be a wonderfully lonely and silent day on the trail. Before ever really settling in, I left another temporary home behind and headed to Hawksbill Summit, the highest mountain in the park.

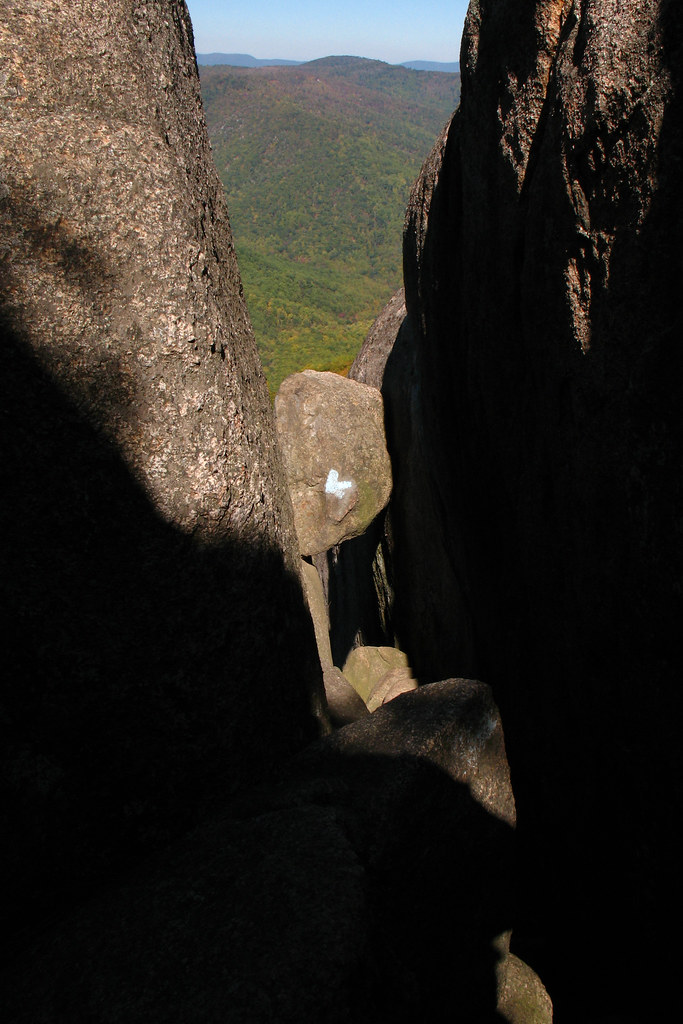

A blanket of low gray clouds began to slip under the cheery coral ones, essentially ending any chance that the sun’s rays would chase away the chill; it was sure to be a wonderfully lonely and silent day on the trail. Before ever really settling in, I left another temporary home behind and headed to Hawksbill Summit, the highest mountain in the park.The more I ascended to the top, the more the local fauna changed from tall trees and soft fluttering leaves to short ridged species with stern roots and needle-covered stems. Dead leaves that were probably still clinging to shrubs just a few days ago, sat at the base of bundled bare stems.

At the summit, the growing fog reduced visibility, but I could still see to the valley below. The treetops draped the rolling hills in specks of green, orange, gold, and brown, like bed pillows lumped together under the afghan your grandma knitted in 1963.

At the summit, the growing fog reduced visibility, but I could still see to the valley below. The treetops draped the rolling hills in specks of green, orange, gold, and brown, like bed pillows lumped together under the afghan your grandma knitted in 1963. The receding mountain soil revealed a brown stone scalp with gray splotches of lichen and an assemblage of protruding jagged edges. I wandered around looking for a place to sit. I discovered a concaved portion in the rock where a puddle formed. There hasn’t been a convenient water source for a while and my supply was bone dry. The water looked clear, but on top floated a few insect cadavers (i.e. protein water). I filled up a plastic bottle just in case I got desperate. Having been dehydrated on the trail before, I learned to always have at least one bottle at hand, no matter how confident you are about future water sources.

The receding mountain soil revealed a brown stone scalp with gray splotches of lichen and an assemblage of protruding jagged edges. I wandered around looking for a place to sit. I discovered a concaved portion in the rock where a puddle formed. There hasn’t been a convenient water source for a while and my supply was bone dry. The water looked clear, but on top floated a few insect cadavers (i.e. protein water). I filled up a plastic bottle just in case I got desperate. Having been dehydrated on the trail before, I learned to always have at least one bottle at hand, no matter how confident you are about future water sources. I sat my camera on one of the boulders and set the timer to take my picture at roughly the highest point in Shenandoah National Park. I hiked back down to the Appalachian Trail and continued north.

I sat my camera on one of the boulders and set the timer to take my picture at roughly the highest point in Shenandoah National Park. I hiked back down to the Appalachian Trail and continued north.Every time the trail descended, my hiking poles double as orthopedic canes to take weight off my right knee. The pain began to worry me. Not because I wouldn’t get to my car, it wasn’t that debilitating, but because I hope to have at least another 35 years of backpacking in me. I can’t have my body failing already. I would skip the remaining side trails and summits to keep my mileage at a minimum. Getting to my car today, and thus having an extra day to recover at home, was beginning to look like the smart choice.

Shortly after giving in and drinking sterilized “protein water”, I heard the unmistakable gurgling sound of a flowing stream. I didn’t see anything at first, but as I approached the source and kicked aside some dried leaves, I found clean water flowing from an opening in the side of the hill. At two feet from the trail, only a standing drinking fountain would have been more convenient. The only downside to this discovery was that now the bug in my teeth was completely unnecessary.

Shortly after giving in and drinking sterilized “protein water”, I heard the unmistakable gurgling sound of a flowing stream. I didn’t see anything at first, but as I approached the source and kicked aside some dried leaves, I found clean water flowing from an opening in the side of the hill. At two feet from the trail, only a standing drinking fountain would have been more convenient. The only downside to this discovery was that now the bug in my teeth was completely unnecessary.The fog continued to thicken and had soon condensed the views to mostly foreground. When one side of the trail would open to a sharply descending view into the valley, I saw nothing but white. I turned to look directly into it and it nearly filled my full view. Knowing that mountains and a valley floor was somewhere hundreds of yards beyond it made the white fog imposing, like swimming in a murky lake that you know is deep, but you can’t see to the bottom.

Even though the fog limited my view, it made the colors nearer to me stand out even more. The remaining miles on the Appalachian ridge were edged in the entire Crayola catalog: Granny Smith Apple ferns, leaves of Sunset Orange, Harvest Gold, Asparagus Green, and Goldenrod, and dead leaves and twigs of Raw Umber, Mahogany, and Burnt Sienna. All that was missing was a sky of Periwinkle or Cornflower Blue.

Somewhere in the fog, I heard voices, faint and muffled. For a time they seemed to hover around in the white void. As I closed in behind them, they eventually became louder and intelligible. A three-generation Italian family came into view, hiking single file down the narrow trail in front of me. I joined them at the back of the line.

The middle generation son and father, who incidentally looked like a good person to have standing behind you if you ever needed to look intimidating, told the others to let me pass. While doing so, his questions trapped me in the middle of their convoy. He was in that category of people who are surprised to learn that anyone would solo backpack for a whole week. Regardless of the man’s presence, he was kind, jovial, and “would never hike alone out here”.

I asked them if they heard any weather reports recently. “Ninety percent chance of rain tonight and supposed to be colder”. They offered to feed me when returning to the picnic area, and under different circumstances I would love to have let them. I mean, unless the Olive Garden commercials have lied to me, Italians have a hell of a lot of fun at the dinner table. I thanked them but declined. I decided I needed to finish my journey today.

The temperature continued to drop as promised, intensified by a mist in the air that clung to any exposed skin. My knee continued to throb. I stopped to eat when I came upon a shelter with a large brick chimney in its center and picnic tables on each of its four sides. The break was more about getting out of the weather and off my knee than to eat.

With the chimney shielding me from the wind, I set my pack on the table and pulled out my food. My knee ached and popped like some geriatric as I sat down.

A couple of cars drove through the picnic area, taking in the limited view from heated vehicles, but nobody ever got out. I felt like I had the entire park to myself. If the cost of this luxury was having my teeth chatter anytime I stopped focusing on preventing them, it was worth it.

A few miles later I took my final rest at a three-walled AT shelter before hobbling down the final couple of miles. On a picnic table sat an AT log book. I read entries from both day hikers and those of the more adventurous attempting a hike of the entire 2,200 mile trail.

Not long after leaving the shelter, I passed a couple doing just that. I knew it before talking to them; the youthful twenty-something face peeking through a long gnarly beard gave it away. “How long have you been on the trail?” I asked.

“Three months,” the beard said.

“Ah, I thought you might be thru-hikers.”

They began their journey at Mount Katahdin in Maine and would put one foot in front of the other until they reached Springer Mountain in Georgia. It was easy to see he didn’t want to stop long to chat. It had been several days since they have seen a camp store and seemed frustrated because of that. Stopping them to ask questions didn't help. I assured them they would get to one tomorrow.

The girl gave me their blog address so I could follow their progress. He glared at her with eyes that seemed to say, “Are you crazy? We don’t know this potentially murderous jackass.” So, I wished them luck and went on my way. I envied their journey like most people envy the rich. If a week in the woods can transform me as it has, what would 25 weeks do?

They reached the summit of Springer Mountain two months later and 2,178 miles from where they began.

When I reached the end of my own much shorter trip, I felt a sort of gladness at first. I could finally get off my knee and get out of the rain and warm up. But it felt odd to be in my car again, like I haven’t seen it for weeks. I sat in its comfortable seat, turned on the heat, and pulled onto Skyline drive for a nine hour trip back home.

Going from trail, to car, to road, and thus officially ending my trip, happened too quickly. I had been thrust back into my normal life in an instant. There wasn’t a sense of finality, no feeling that I had finished my task, and yet, here I was heading home. It was still nice to be off my knee and warm, but much of that gladness faded when passing the park sign thanking me for my visit.

Pulling out on the highway made me feel like the man being air rescued, in every book or movie about a solitary person getting stranded on a deserted island. He thought it would be great to head back to the comfort and safety of civilization, but realizes he’s grown attached to the wilderness and part of him misses it already.

Just then an enormous black bear barreled out of the woods a safe distance in front of my car. I had never seen one moving at full speed like that. Here was confirmation that there would be no outrunning one if I ever tried, no photo finish, not even close. In a few seconds, it galloped across four lanes of highway, then disappeared into the woods on the other side.

Clearly that wild world I was leaving would carry on just fine without me, but I didn’t want it to have to. Not only was I not ready to leave the gratifying and uncomplicated life on the trail, I mostly wasn’t ready to stop being the person I became while out there. I wasn’t only leaving the wilderness behind, but the version of myself that I like the most. The version of me that is imperviously happy and contented to simply wander and wonder. It is increasingly difficult after every trip, to return to the routine and maintain any resemblance to that backpacking frame of mind.

A few days later, I walked out of the factory where I work. When I pushed the door open I felt cold crisp air and began to breathe it in like so many mornings in Shenandoah, but soon noticed it blend with the smell of heat, burning resin, and wire that wafted out of ventilation ducts. It wasn’t the satisfying deep breath I, for some reason, was expecting.

I walked down the long straight parking lot edged with cars. On my right, a large flock of birds were gathered in the grass. They scattered when I got near them. Dozens of black birds soared through the air like they shared one mind. I felt an instant desire to join them. My heart rate increased. I was ready to be wild like them once again. To take off my uncomfortable shoes and run into the nearest woods, and, as Thoreau said, “live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived." The feeling pushed at my chest.

I need to be in the wilderness, I thought, away from the murmur and clang of an active factory floor and the monotony of my everyday life.

Soon, and as it always does, the strength of that feeling started to drift away like dandelion spores. I fully returned to my old self. At some point I decided my life is going pretty good, and it truly is, as good as it has ever been actually. Good enough to not risk it with a major change? As I write this I’m still uncertain of the answer to that question, but I continue to have this longing that a couple of weeks on the trail per year can’t pacify. Will I ever gain the courage to embark on my own 2,178 mile adventure?

Soon, and as it always does, the strength of that feeling started to drift away like dandelion spores. I fully returned to my old self. At some point I decided my life is going pretty good, and it truly is, as good as it has ever been actually. Good enough to not risk it with a major change? As I write this I’m still uncertain of the answer to that question, but I continue to have this longing that a couple of weeks on the trail per year can’t pacify. Will I ever gain the courage to embark on my own 2,178 mile adventure?I watch as my time on earth slowly collects like gathering droplets of water. The seconds accumulate like insignificant raindrops on leaves, which pour into puddles of minutes, and flood into hour-filled lakes. The years flow downstream like rivers carving the landscape. Some rivers simply erode. Some flow underground forever unseen. But some create grand canyons that endure for ages and inspire long after they’re gone. Is my time better spent in contentment and safety or with the risk of adventure? How do I want my river to flow before it quietly drifts into that eternally endless ocean?

There are many questions I wish I knew how to answer, but as I reflect on that autumn week in Shenandoah and those daily escalations of joy, introspection, and wonder, there is one revelation that I have had. John Muir was right: a week in the woods is not enough.

There are many questions I wish I knew how to answer, but as I reflect on that autumn week in Shenandoah and those daily escalations of joy, introspection, and wonder, there is one revelation that I have had. John Muir was right: a week in the woods is not enough.Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

-RG

See all my posted photos from this trip

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.