Part Six: Thursday’s Blissfulness

Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

“Nothing can be done well at a speed of forty miles a day.

Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

“Nothing can be done well at a speed of forty miles a day.

Far more time should be taken. Walk away quietly in any

direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Climb

the mountains and get their good tidings. Nature's peace

will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds

will blow their own freshness into you, and the storms their

energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves."

- John Muir

Today my mood shifted from happiness towards blissfulness. On day one I was cold and frustrated; now it’s warm and I have an almost childlike giddiness.

Today my mood shifted from happiness towards blissfulness. On day one I was cold and frustrated; now it’s warm and I have an almost childlike giddiness.

This afternoon I’d set foot on the Appalachian Trail and fulfill number 13 on my life list, “Hike Overnight on the Appalachian Trail”. (Not to be confused with number 14, “Hike the entire 2,200 mile Appalachian Trail.” Some dreams need to be big.) First, I would finish my waterfall tour on the Rose River Falls loop, Dark Hollow Falls Trail, and then see my final Shenandoah waterfall on the Lewis Falls Trail.

I stopped frequently this morning as I found the beauty of the area incredible, not that it was any better than before, but it was exaggerated by my exceedingly good mood. At my first rest stop I sat on the ground with the pack beside me and my journal in my hand. I stared at a fern sitting on top of an algae covered boulder. Its leaves dangled over the edge inches above the water. A single yellow leaf caught my eye when it fluttered to the creek below. Days alone in nature give you time to closely examine such things. I contemplated the leaf's ephemeral existence.

Throughout its life, it was the flowers that got the attention, but now its color rivaled that of any petal. In its peak of loveliness, a breeze detaches it from its branch, sending it spiraling into black mirrored water. Lazily, it floats down the stream. The calmness occasionally interrupted by short burst of speed, as it is poured over cascading stair steps. Along the creek’s edge it stops, in a place with no significance. It is here that it will wait to return to atoms, nourish the soil and become something new again. Not at all an empty existence.

All things are fated to decay: fallen leaves and human beings. I know this may sound gloomy, but it isn’t meant to; rather it should be humbling and motivating. The atoms will become part of tomorrow’s trees, forest soil, bear cubs, and breathtaking views. So, everything is worthy of our reverence, and nothing should be taken for granted. While I can, I’ll collect these moments like fine jewels, cherish them, and share them with others.

Paying attention to these details has become second nature. I am not the man I was last week, or even yesterday. I am a man that is noticing the simplest things, the breezes, the softest sounds, the life of a single yellow leaf.

As much as I love the writings of John Muir (especially the quote above) and many others like him, I'd have to say it’s the scientists that have inspired me the most. Give me the words of Muir or Emerson, but not without the passion of Carl Sagan or the endless curiosity of E.O. Wilson. I owe much of my love of nature to scientists and find immense joy in learning about the natural world, but this morning I gloried in the life of a tree, without any consideration for the process of photosynthesis. I simply sat and paid attention.

This was a time that I will always remember when I hear the word Shenandoah. Sitting there alone in the early morning, I felt this almost indescribable feeling of joy. An even stronger feeling than I had on Tuesday afternoon. The solitude, beauty and simplicity has filled me up so much, it seemed the only way I could release the pressure was through tears. I closed my watered eyes, released the air from my lungs, and a weight seemed to lift away from my chest that I didn’t realize was there until it was gone.

In only the rarest of moments have I been this happy. If there were ever a time in my life where I could have produced an absolute perfect Care Bear Stare, this was it.

I pulled out my journal and tried to scribble down any words that would describe how I felt, but I’m not poetic enough to justify it, nor did any of the words in my vocabulary seem to fit. The last line I wrote however was, “Note to self: devote your life to the national parks.”

I didn’t know exactly what that meant. I felt like I wanted, actually needed, to quit my job, go back to school and become a park ranger or something. I'm not quite sure, but I definitely knew I wanted to dedicate more time to these aimless wanderings through natural worlds, while noticing the brilliance of something as simple as a falling leaf. It meant I wanted to be a part of the never-ending struggle to protect these remaining wild places, so others would grow to understand why they are necessary, to convince them to spend more time in them. So few allow themselves to be all alone in nature for even one night, let alone the many nights required to understand this feeling that has become so profoundly important to me.

A couple strolling down the trail, asked the obligatory, “How you doing?”

A couple strolling down the trail, asked the obligatory, “How you doing?”

“Never better,” was my reply.

At Dark Hollow Falls, I stopped for a photo and checked my map. I see I’m coming up to a black square with a white letter P written inside. I know this symbol stands for Parking, but for me it meant People, since most don’t venture far from their car. As much as I don’t understand why, and as much as I want to convince people to head deeper into the backcountry, there is some good in it. The deep woods are left empty where the only life you come across are wild animals, and the occasional silent devotee of solitude and nature. In fact, I’m grateful for this solitude because without it, this fantastic morning, one that I’ll remember forever, probably wouldn’t have existed.

Higher up the falls, a crowd of people were packed together taking pictures, resting before their short hike back to the letter P. I wandered through the crowd looking at faces, feeling enlightened, like I knew something special about this place that they did not. And perhaps I did.

After passing the parking lot and crossing over a road, the number of people dwindled considerably. Only two remained, which were heading back to their campground. The trail, and forest, now seemed to be relatively new. Saplings grew inside protective cages and the trail still had grasses trying to poke through.

Another white-tailed deer stood in my path, grazing with her fawn. As before, they stared at me with those glistening trustful eyes for a few seconds then put their heads back down to eat. I pulled out my camera and took several photos. I moved slowly, to keep them from bouncing away into the forest, as I watched them through my camera’s LCD display. Sometimes I wonder if I watch too much through my camera, trying to preserve memories rather than completely living them.

The path now looked different from the map I held in front of me. My intersection should be around here, but I wasn’t seeing it. To find my bearings, I hiked a little further to a road which led to the campground. I circled the area for fifteen minutes when I met a couple who too were lost.

The young woman was certain she saw a signpost for my trail a quarter-mile back, near where I had just hiked. I show them our location on the map and point to what they were looking for, that same little black square with the white letter P. So, the three of us backtracked in that direction. They seemed interested in what I was doing. Which I admit I love because on our short hike together, I got to talk about backpacking and the places I’ve been.

We came to my intersection, which had two large and plainly visible signs. I saw wire cages protecting saplings and two grazing deer, then realized I missed the intersection while staring into the camera’s LCD display earlier. The answer to my question was, yes, I do watch too much through the lens of my camera.

The feeling of stupidity was fortunately masked by the confidence of being back on track. I trekked along at a good pace to make up some time, but froze suddenly when I caught an adult black bear in the corner of my eye, 40-feet from the trail.

I slowly turned to look at it scratching the ground in search of grubs. The bear seemed pleasant and affable enough. It definitely didn’t care about what I was doing, so instead of sanely continuing down the trail, I just stood there transfixed. Much like the deer, it gave me a somber look for a few seconds, and then continued poking is nose through the dried leaves on the ground. I would still never approach one, but any fear I had of these creatures diminished.

According to my map, a park restaurant was nearby. I initially didn’t want to leave the trail and join the civilized world, but decided everyone needs the occasional cheeseburger detour. I stopped at a trashcan by the entrance and rid my pack of extra garbage weight, because every ounce matters when you’re a human pack mule.

“You a thru hiker?” a grubby pot-bellied man exiting the restaurant asked while sucking the leftovers from his teeth. By thru hiker, he was asking if I was hiking the entire 2,200-mile Appalachian Trail.

“No, just here for the week.”

“How many miles you gone?”

“Uhh, almost fifty, I think.” He didn't seem impressed, not that he should have been as it wasn't an impressive pace. I know of people doubling and some even tripling this pace, but you meet two types of people on the trail, those shocked to hear you’ve been hiking alone all week, and those with experience backpacking (or experience talking to backpackers) that think of fifty miles as no more than a nice traipse through the woods.

I put my pack back on and headed through the double doors. The building split into sections: souvenirs on my left, a camp store straight ahead, and the restaurant to my right. The restaurant was crammed with tourists. I didn’t trust leaving my gear out of sight this far from my car, so I stood in line with it on, bumping into people and drawing some attention.

“Your combos are too big for us. We’re going to share one cheeseburger combo and add a drink,” said a woman with her husband at the front of the line. He told her what he wanted to drink and then she told the girl behind the counter for him, as if he was a child. But all I focused on at the time was, “Ooh, cheeseburger combo that’s too big for one adult human being? Do I need one or two?”

I’ll remember my personal rule to limit beef intake when I’m back at home. I have tried on several occasions to completely become a vegetarian, but I can never keep it up for long. I think if I ever utter the phrase, “this is my last cheeseburger,” I will collapse like a marionette in a puddle of tears. Overdramatic yes, but an accurate portrayal.

I walked away from the crowded building, found a tree to sit under, and devoured the calorific sandwich. The lettuce, tomato, and onion struggled to stay under the bun, slipping on ketchup, mustard and melted cheese. I ate every bit including the parts that fell off and the cheese stuck to the wrapper. Grease and condiments slathered my lips like an infant enjoying his first birthday cake.

Backpacking, or maybe its deprivation, makes any food taste better. The savory burger could have been peanut butter and jelly and would have been incredible. Either way, it was an order of magnitude better than if I was eating lunch at work right now. In fact, right about now on a normal week I’d probably be picking peas out of the cherry vanilla crisp section of a healthy choice meal.

I left the populated area, and made my way back to solitude and my final waterfall view, Lewis Falls. Miles later I came to the Appalachian Trail intersection and pulled out my camera. I needed to document the moment. I reached out and touched my first AT white blaze, a well known marker on trees along the AT that let backpackers know they are still on course.

I left the populated area, and made my way back to solitude and my final waterfall view, Lewis Falls. Miles later I came to the Appalachian Trail intersection and pulled out my camera. I needed to document the moment. I reached out and touched my first AT white blaze, a well known marker on trees along the AT that let backpackers know they are still on course.

I was near a park campground when an elderly couple passed by on their late afternoon stroll. They saw my hiking poles and backpack and seemed incredibly excited to ask me about what I was doing. It was as though they’ve never heard of such things.

“You’re out here alone? For a whole week? And all you have is what’s in that backpack? Where do you get water? Do you sleep in a tent? A hammock, really? That’s amazing. I don’t think I could do that.”

I really enjoyed the company of these people.

As I rounded the campground I saw another black bear. It was much larger than the previous. I wanted to get the attention of the campers nearby so they wouldn’t miss it. The campground felt like a mobile home village. A clearcut section of forest filled in by heat absorbing blacktop, the stench of pit toilets, and oily automobile engines. A couple, probably in their 30s, sat on folding camp chairs angled towards the woods. A few yards beside them sat a car, a road, and a park dumpster. They couldn’t see the bear. Surrounded by nature, but still limiting themselves to the confines of their rented rectangle of land. It kind of made me sad. You've come so far, don’t stop now, you’re going to go home without seeing Shenandoah.

I decided to do the bear a favor and never pointed him out to any of the campers.

My hike along the Appalachian ridge was gorgeous at every step. The sun was setting, but I couldn’t keep myself from stopping at every view of the valley, and there were many. I moved forward until daylight was nearly gone and finally stopped to setup camp about fourteen miles from where I started this morning.

I turned off the trail and hiked into the woods looking for a clearing. A few hundred feet in, I decided I would hang my bear bag while I still had some light. While rushing, I got my rope and counterweight stuck in a tree. It took thirty minutes to get it back down. By the time I got to my camp site, the sun was long gone. I setup camp by the light of my headlamp.

I turned off the trail and hiked into the woods looking for a clearing. A few hundred feet in, I decided I would hang my bear bag while I still had some light. While rushing, I got my rope and counterweight stuck in a tree. It took thirty minutes to get it back down. By the time I got to my camp site, the sun was long gone. I setup camp by the light of my headlamp.

The night was not unlike the others. Only now, I was talking to myself more regularly (another feature of the solo backpacker after a few days). I was glad to get off my aching right knee, which I knew would make the final miles difficult, but every uncomfortable step today was worth it. It was one of the best days I've ever had. I stayed up late in the hammock to finish my book about serial killers, often times reading aloud, and yes, doing different character voices, until it weighed on my eyelids.

Part 7 >

Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

- John Muir

Today my mood shifted from happiness towards blissfulness. On day one I was cold and frustrated; now it’s warm and I have an almost childlike giddiness.

Today my mood shifted from happiness towards blissfulness. On day one I was cold and frustrated; now it’s warm and I have an almost childlike giddiness.This afternoon I’d set foot on the Appalachian Trail and fulfill number 13 on my life list, “Hike Overnight on the Appalachian Trail”. (Not to be confused with number 14, “Hike the entire 2,200 mile Appalachian Trail.” Some dreams need to be big.) First, I would finish my waterfall tour on the Rose River Falls loop, Dark Hollow Falls Trail, and then see my final Shenandoah waterfall on the Lewis Falls Trail.

I stopped frequently this morning as I found the beauty of the area incredible, not that it was any better than before, but it was exaggerated by my exceedingly good mood. At my first rest stop I sat on the ground with the pack beside me and my journal in my hand. I stared at a fern sitting on top of an algae covered boulder. Its leaves dangled over the edge inches above the water. A single yellow leaf caught my eye when it fluttered to the creek below. Days alone in nature give you time to closely examine such things. I contemplated the leaf's ephemeral existence.

Throughout its life, it was the flowers that got the attention, but now its color rivaled that of any petal. In its peak of loveliness, a breeze detaches it from its branch, sending it spiraling into black mirrored water. Lazily, it floats down the stream. The calmness occasionally interrupted by short burst of speed, as it is poured over cascading stair steps. Along the creek’s edge it stops, in a place with no significance. It is here that it will wait to return to atoms, nourish the soil and become something new again. Not at all an empty existence.

All things are fated to decay: fallen leaves and human beings. I know this may sound gloomy, but it isn’t meant to; rather it should be humbling and motivating. The atoms will become part of tomorrow’s trees, forest soil, bear cubs, and breathtaking views. So, everything is worthy of our reverence, and nothing should be taken for granted. While I can, I’ll collect these moments like fine jewels, cherish them, and share them with others.

Paying attention to these details has become second nature. I am not the man I was last week, or even yesterday. I am a man that is noticing the simplest things, the breezes, the softest sounds, the life of a single yellow leaf.

As much as I love the writings of John Muir (especially the quote above) and many others like him, I'd have to say it’s the scientists that have inspired me the most. Give me the words of Muir or Emerson, but not without the passion of Carl Sagan or the endless curiosity of E.O. Wilson. I owe much of my love of nature to scientists and find immense joy in learning about the natural world, but this morning I gloried in the life of a tree, without any consideration for the process of photosynthesis. I simply sat and paid attention.

This was a time that I will always remember when I hear the word Shenandoah. Sitting there alone in the early morning, I felt this almost indescribable feeling of joy. An even stronger feeling than I had on Tuesday afternoon. The solitude, beauty and simplicity has filled me up so much, it seemed the only way I could release the pressure was through tears. I closed my watered eyes, released the air from my lungs, and a weight seemed to lift away from my chest that I didn’t realize was there until it was gone.

In only the rarest of moments have I been this happy. If there were ever a time in my life where I could have produced an absolute perfect Care Bear Stare, this was it.

I pulled out my journal and tried to scribble down any words that would describe how I felt, but I’m not poetic enough to justify it, nor did any of the words in my vocabulary seem to fit. The last line I wrote however was, “Note to self: devote your life to the national parks.”

I didn’t know exactly what that meant. I felt like I wanted, actually needed, to quit my job, go back to school and become a park ranger or something. I'm not quite sure, but I definitely knew I wanted to dedicate more time to these aimless wanderings through natural worlds, while noticing the brilliance of something as simple as a falling leaf. It meant I wanted to be a part of the never-ending struggle to protect these remaining wild places, so others would grow to understand why they are necessary, to convince them to spend more time in them. So few allow themselves to be all alone in nature for even one night, let alone the many nights required to understand this feeling that has become so profoundly important to me.

A couple strolling down the trail, asked the obligatory, “How you doing?”

A couple strolling down the trail, asked the obligatory, “How you doing?”“Never better,” was my reply.

At Dark Hollow Falls, I stopped for a photo and checked my map. I see I’m coming up to a black square with a white letter P written inside. I know this symbol stands for Parking, but for me it meant People, since most don’t venture far from their car. As much as I don’t understand why, and as much as I want to convince people to head deeper into the backcountry, there is some good in it. The deep woods are left empty where the only life you come across are wild animals, and the occasional silent devotee of solitude and nature. In fact, I’m grateful for this solitude because without it, this fantastic morning, one that I’ll remember forever, probably wouldn’t have existed.

Higher up the falls, a crowd of people were packed together taking pictures, resting before their short hike back to the letter P. I wandered through the crowd looking at faces, feeling enlightened, like I knew something special about this place that they did not. And perhaps I did.

After passing the parking lot and crossing over a road, the number of people dwindled considerably. Only two remained, which were heading back to their campground. The trail, and forest, now seemed to be relatively new. Saplings grew inside protective cages and the trail still had grasses trying to poke through.

Another white-tailed deer stood in my path, grazing with her fawn. As before, they stared at me with those glistening trustful eyes for a few seconds then put their heads back down to eat. I pulled out my camera and took several photos. I moved slowly, to keep them from bouncing away into the forest, as I watched them through my camera’s LCD display. Sometimes I wonder if I watch too much through my camera, trying to preserve memories rather than completely living them.

The path now looked different from the map I held in front of me. My intersection should be around here, but I wasn’t seeing it. To find my bearings, I hiked a little further to a road which led to the campground. I circled the area for fifteen minutes when I met a couple who too were lost.

The young woman was certain she saw a signpost for my trail a quarter-mile back, near where I had just hiked. I show them our location on the map and point to what they were looking for, that same little black square with the white letter P. So, the three of us backtracked in that direction. They seemed interested in what I was doing. Which I admit I love because on our short hike together, I got to talk about backpacking and the places I’ve been.

We came to my intersection, which had two large and plainly visible signs. I saw wire cages protecting saplings and two grazing deer, then realized I missed the intersection while staring into the camera’s LCD display earlier. The answer to my question was, yes, I do watch too much through the lens of my camera.

The feeling of stupidity was fortunately masked by the confidence of being back on track. I trekked along at a good pace to make up some time, but froze suddenly when I caught an adult black bear in the corner of my eye, 40-feet from the trail.

I slowly turned to look at it scratching the ground in search of grubs. The bear seemed pleasant and affable enough. It definitely didn’t care about what I was doing, so instead of sanely continuing down the trail, I just stood there transfixed. Much like the deer, it gave me a somber look for a few seconds, and then continued poking is nose through the dried leaves on the ground. I would still never approach one, but any fear I had of these creatures diminished.

According to my map, a park restaurant was nearby. I initially didn’t want to leave the trail and join the civilized world, but decided everyone needs the occasional cheeseburger detour. I stopped at a trashcan by the entrance and rid my pack of extra garbage weight, because every ounce matters when you’re a human pack mule.

“You a thru hiker?” a grubby pot-bellied man exiting the restaurant asked while sucking the leftovers from his teeth. By thru hiker, he was asking if I was hiking the entire 2,200-mile Appalachian Trail.

“No, just here for the week.”

“How many miles you gone?”

“Uhh, almost fifty, I think.” He didn't seem impressed, not that he should have been as it wasn't an impressive pace. I know of people doubling and some even tripling this pace, but you meet two types of people on the trail, those shocked to hear you’ve been hiking alone all week, and those with experience backpacking (or experience talking to backpackers) that think of fifty miles as no more than a nice traipse through the woods.

I put my pack back on and headed through the double doors. The building split into sections: souvenirs on my left, a camp store straight ahead, and the restaurant to my right. The restaurant was crammed with tourists. I didn’t trust leaving my gear out of sight this far from my car, so I stood in line with it on, bumping into people and drawing some attention.

“Your combos are too big for us. We’re going to share one cheeseburger combo and add a drink,” said a woman with her husband at the front of the line. He told her what he wanted to drink and then she told the girl behind the counter for him, as if he was a child. But all I focused on at the time was, “Ooh, cheeseburger combo that’s too big for one adult human being? Do I need one or two?”

I’ll remember my personal rule to limit beef intake when I’m back at home. I have tried on several occasions to completely become a vegetarian, but I can never keep it up for long. I think if I ever utter the phrase, “this is my last cheeseburger,” I will collapse like a marionette in a puddle of tears. Overdramatic yes, but an accurate portrayal.

I walked away from the crowded building, found a tree to sit under, and devoured the calorific sandwich. The lettuce, tomato, and onion struggled to stay under the bun, slipping on ketchup, mustard and melted cheese. I ate every bit including the parts that fell off and the cheese stuck to the wrapper. Grease and condiments slathered my lips like an infant enjoying his first birthday cake.

Backpacking, or maybe its deprivation, makes any food taste better. The savory burger could have been peanut butter and jelly and would have been incredible. Either way, it was an order of magnitude better than if I was eating lunch at work right now. In fact, right about now on a normal week I’d probably be picking peas out of the cherry vanilla crisp section of a healthy choice meal.

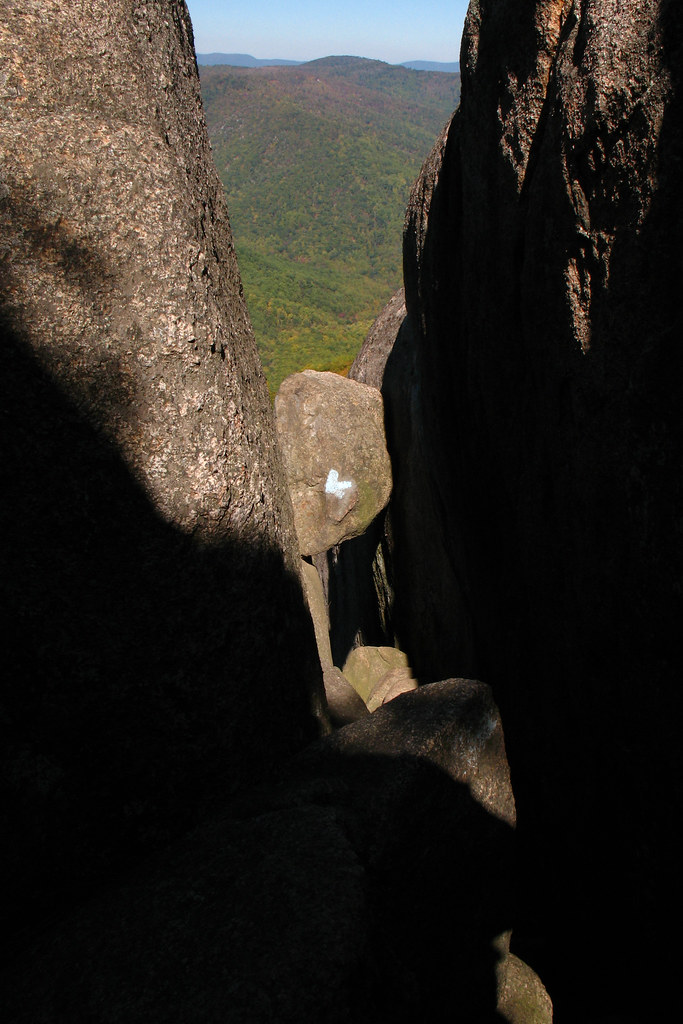

I left the populated area, and made my way back to solitude and my final waterfall view, Lewis Falls. Miles later I came to the Appalachian Trail intersection and pulled out my camera. I needed to document the moment. I reached out and touched my first AT white blaze, a well known marker on trees along the AT that let backpackers know they are still on course.

I left the populated area, and made my way back to solitude and my final waterfall view, Lewis Falls. Miles later I came to the Appalachian Trail intersection and pulled out my camera. I needed to document the moment. I reached out and touched my first AT white blaze, a well known marker on trees along the AT that let backpackers know they are still on course. |

| My first AT white blaze |

“You’re out here alone? For a whole week? And all you have is what’s in that backpack? Where do you get water? Do you sleep in a tent? A hammock, really? That’s amazing. I don’t think I could do that.”

I really enjoyed the company of these people.

As I rounded the campground I saw another black bear. It was much larger than the previous. I wanted to get the attention of the campers nearby so they wouldn’t miss it. The campground felt like a mobile home village. A clearcut section of forest filled in by heat absorbing blacktop, the stench of pit toilets, and oily automobile engines. A couple, probably in their 30s, sat on folding camp chairs angled towards the woods. A few yards beside them sat a car, a road, and a park dumpster. They couldn’t see the bear. Surrounded by nature, but still limiting themselves to the confines of their rented rectangle of land. It kind of made me sad. You've come so far, don’t stop now, you’re going to go home without seeing Shenandoah.

I decided to do the bear a favor and never pointed him out to any of the campers.

My hike along the Appalachian ridge was gorgeous at every step. The sun was setting, but I couldn’t keep myself from stopping at every view of the valley, and there were many. I moved forward until daylight was nearly gone and finally stopped to setup camp about fourteen miles from where I started this morning.

I turned off the trail and hiked into the woods looking for a clearing. A few hundred feet in, I decided I would hang my bear bag while I still had some light. While rushing, I got my rope and counterweight stuck in a tree. It took thirty minutes to get it back down. By the time I got to my camp site, the sun was long gone. I setup camp by the light of my headlamp.

I turned off the trail and hiked into the woods looking for a clearing. A few hundred feet in, I decided I would hang my bear bag while I still had some light. While rushing, I got my rope and counterweight stuck in a tree. It took thirty minutes to get it back down. By the time I got to my camp site, the sun was long gone. I setup camp by the light of my headlamp.The night was not unlike the others. Only now, I was talking to myself more regularly (another feature of the solo backpacker after a few days). I was glad to get off my aching right knee, which I knew would make the final miles difficult, but every uncomfortable step today was worth it. It was one of the best days I've ever had. I stayed up late in the hammock to finish my book about serial killers, often times reading aloud, and yes, doing different character voices, until it weighed on my eyelids.

Part 7 >

Go to Part: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7

A Backpacker's Life List by Ryan Grayson is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.